Community means a lot to the people of my country. The culture is seeped with intricate social entanglements that span generations. Although Ethiopia is a third-world country with 23.5% of its inhabitants living under the poverty line, individuals persevere due to the collective effort of the community. Neighbors offer help in times of need, weddings and funerals are a collaborative effort, and holidays are organized to highlight the importance of society. The same communal spirit manifests through the utilization of architecture throughout history.

The architectural interpretation of the communal spirit prevalent in Ethiopian culture can be mapped through generations. As the priorities of the ancient empire evolved so did the the expression of space. The importance of community is especially evident in Harar. Harar is a small city in eastern Ethiopia which was once a renowned Islamic kingdom. The Harari people are known for their hospitality and generous spirit. As evidenced in their vernacular architecture, much importance is placed on the social fabric of the community. People are reliant upon one another to raise children, mourn losses, celebrate good times and partake in religious activities. Neighborhoods (Lasims in the local tongue) are a true portrayal of the importance of community. Each lasim has a group of houses with back to back support and narrow roads that lead to conventional gathering places. The houses often share a courtyard and other utilities. The structural support each house provides for the other is, in my opinion, a poetic interpretation of community. This organization of housing has resulted in the open nature of the residents. The inhabitants are less apprehensive of strangers and willingly share what they have. It is said no house is lacking as long as a neighbor lives.

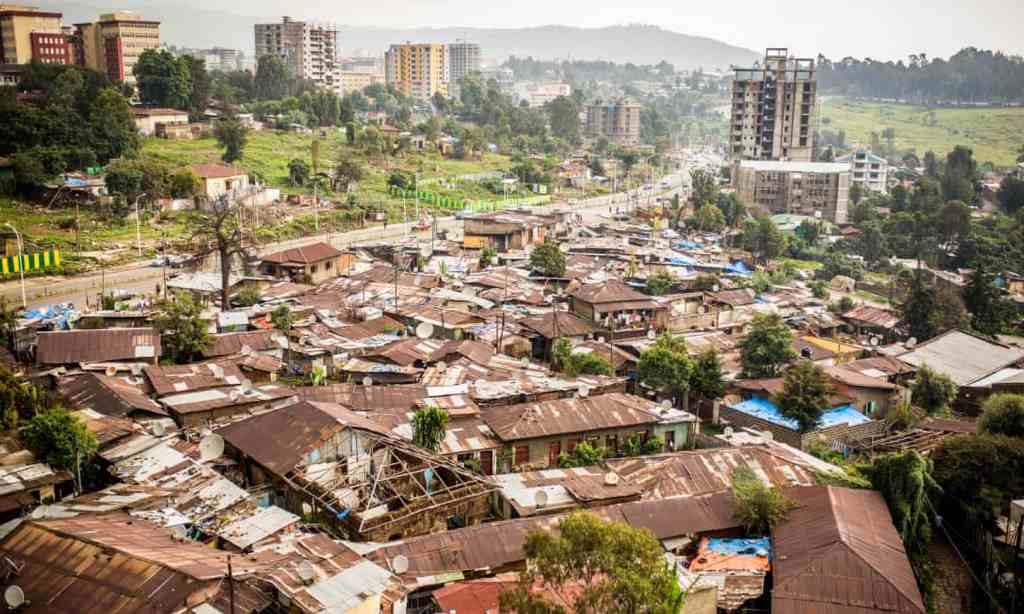

While this practice of co-habitation is an efficient method of fostering strong communal ties, it is thought to be impractical in today’s climate, especially in Addis Ababa where overpopulation is a major concern. I must respectfully disagree. The implemented solution to this looming threat is construction of high-rise housing complexes. While the government’s dedication to provide housing is commendable, the European style construction segregates the residents socially and economically. To quote Alazar Ejigu, architect and urban planner, “the buildings fail to sustain people’s ordinary traditional way of life.” As more people flood into the city and more suburban settlements are established, the once flourishing neighborhoods of central Addis Ababa are being neglected, turned to slums and eventually gentrified. This disrupts the already established social bond of a living community. The residents are often relocated to above mentioned complexes where all semblance of a community is but an inkling. Culture is lost and meaningful interdependence is quashed.

As it is a more permanent form of artistic expression, architecture must play a role in the advancement of societal issues while serving functional needs. It is my hope that architecture will once again contribute to the social fabric of society.