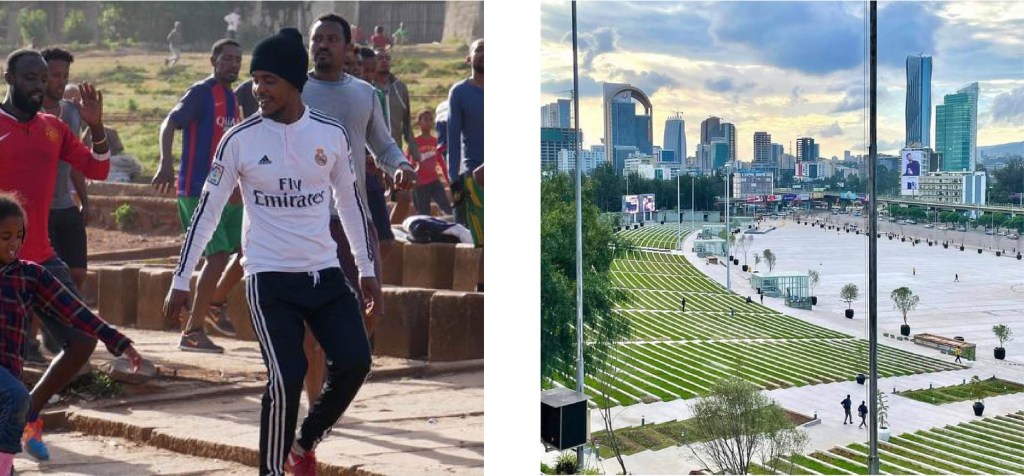

A year after the upload of the of the “beauty” of Meskel square [see below], I am prepared to eat my words. It seems the inaccessibility has now been resolved and was mainly a symptom of the general unrest in the country. At this point, I would like to admit that the new Meskel square can in fact be a viable third-place for the middle class and upper class citizens of the city. Why, you might wonder did I bring up the socio-economic class of users?

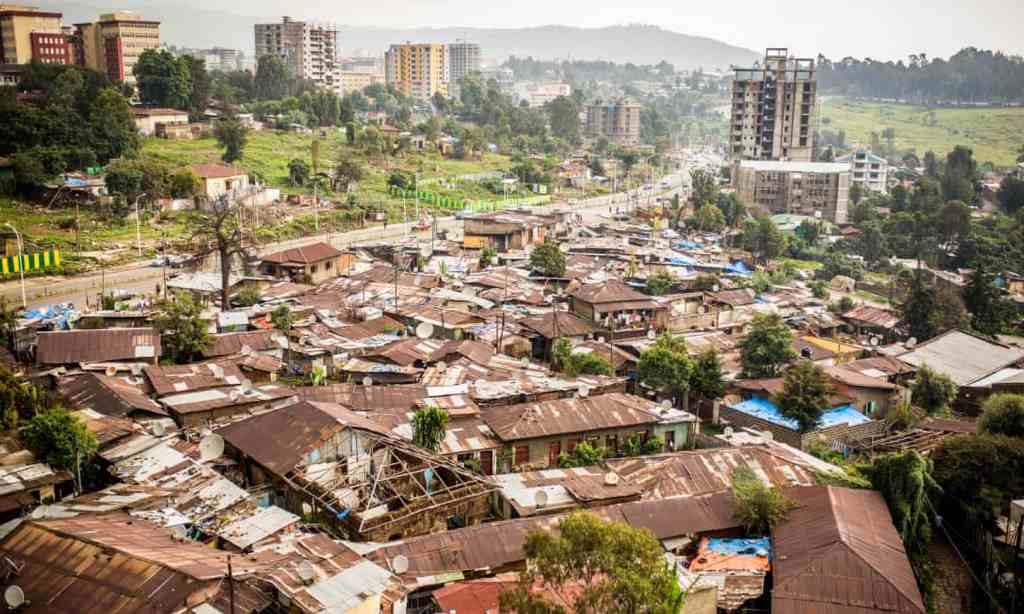

My new-ish argument is the about the exclusivity of beautiful things and the inherent injustice of “improvement”. It is as if there is an implicit barrier in the usership of things perceived beautiful by the greater public. A simple example can be seen in the fashion industry, the service industry and of course in public spaces. Just as beautiful clothes are exclusive to the rich, so are beautiful public spaces. While beautiful is generally a very subjective term, I think a more objective interpretation can be applied to it when it is applied to spaces. one can reasonably argue that a forest is beautiful and a landfill is ugly without attaching the baggage of personal experience. It is with this generalized intention that I call Meskel square beautiful throughout this article. It is as a result of this beauty that the new and “improved” Meskel square inadvertently alienates a large portion of the population.

The argument might be made that it is, for all intensive purposes, open to everyone. But this ignores a fundamental flaw that is perpetuated by its “improvement”. As the program changed from public playground to distinguished hang-out, so has its user. it needn’t be put into words when the visuals speak plenty: this is no place for slumming it. It might seem like I’m arguing that Meskel square needs to go back to its less distinguished status to be welcoming to all, but my point is more a critique of the behavior that reinforces this belief. Well-to-do people feel as if they have a monopoly on comfort and this isn’t challenged by anyone. This is the trend we see in the gentrification of inner city residential areas. Once a place is seen as profitable, comfortable and beautiful, it no longer belongs the undeserving many but to the deserving few. In a capitalist world, improvement to spaces often means taking from the poor in service of the rich. Improved doesn’t only apply to the materials with which the streets are paved but also by the caliber of people who frequent its services.

Meskel square, is in my opinion, emblematic of the follies of the urban improvement mindset and with this Addis Ababa crawls deeper and deeper into the capitalist nightmare its leaders seem to desperately want it to become.